1.2 Positional encoding

Incorporating position related data to word embeddings.

Diagram 1.2.0: The Transformer, Vaswani et al. (2017)

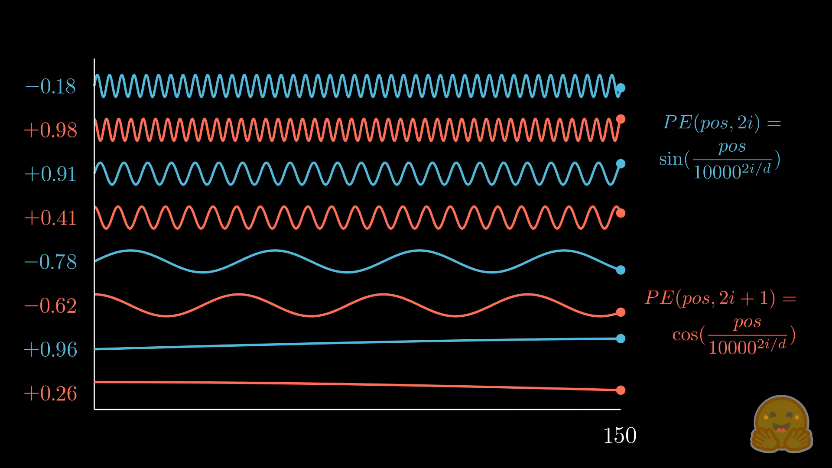

As a Transformer processes the aforementioned tokens in parallel, a method is needed to embed the relative positional data of the tokens into the vector representations. The original Vaswani et al. (2017) paper proposes using the sine and cosine functions as a means of representing positions, alternately for odd and even positions.

Diagram 1.2.1: Generating the positional encoding for a token, and adding it to the vector representation of the token.

Theory

Specifically, positional encodings are generated via the following functions:

k: the position of the object within the input sequence d: set to the same value as the dimension of the word embeddings to be used n: a constant called the scalar, set to 10,000 in Vaswani et al. (2017) i: the output position in regards to the final positional encoding vector that is to be output for a specific token, whereby each set of adjacent odd and even position values are set to the same i, such that

The reasons that positions are encoded via sinusoidal functions are because:

- the functions allow a relative position encoding P+K to derived given the encoding for a specific position P

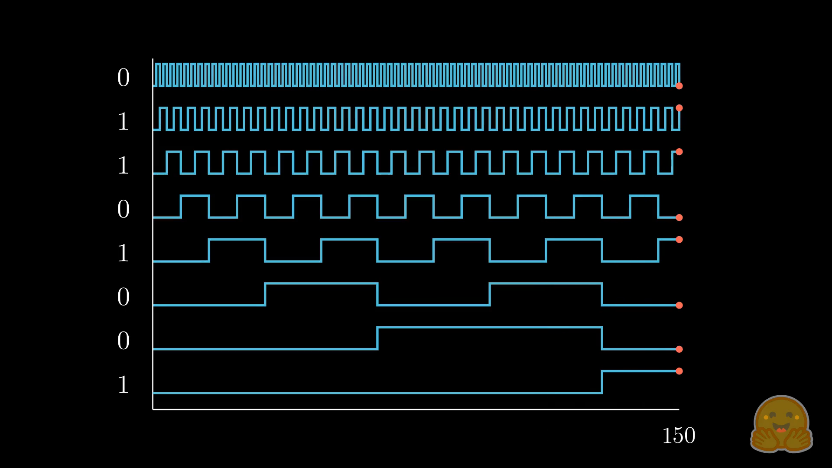

- the functions of alternating wavelengths map relatively closely to binary numbers (see Diagram 1.2.2, 1.2.3), therefore allowing uniqueness (reductionistically, binary numbers are the simplest unique representation)

- the functions are of infinite length, allowing them to be adapted for any input sequence length

- the functions can maintain an output within a limited range (which does not introduce issues with gradient descent during optimisation via loss function)

- the functions can be quickly computed, in a deterministic way, allowing efficiency and dependability

Application of theory

So, for example, generating 16-dimension positional encodings for the input sequence “classify the book”, may look like the following, with n set to 100:

| i | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| classify k = 0 |

0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| the k = 1 |

0.84 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.85 | 0.31 | 0.95 | 0.18 | 0.98 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 1.00 |

| book k = 2 |

0.91 | -0.42 | 0.90 | 0.41 | 0.59 | 0.81 | 0.35 | 0.94 | 0.20 | 0.98 | 0.11 | 0.99 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 1.00 |

| 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.08 | -0.26 | 0.21 | -0.58 | 1.12 | -0.38 | -0.91 | 0.52 | 0.87 | -0.17 | 0.73 | -0.38 | 0.18 |

|---|

+

| 0.91 | -0.42 | 0.90 | 0.41 | 0.59 | 0.81 | 0.35 | 0.94 | 0.20 | 0.98 | 0.11 | 0.99 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 1.00 |

|---|

=

| 0.93 | -0.27 | -0.59 | -.033 | -0.85 | -0.6 | -0.93 | 0.18 | -0.58 | -1.89 | 0.41 | -0.12 | -0.23 | -0.27 | -0.42 | -0.82 |

|---|

This final result, above, is then input into the encoder of the Transformer.

For example, to deduce the position of the token “book” in the above example, knowing where in the vector the number occurs:

However, modern developments have meant that some modern LLMs (including Llama-4[1]) do not use absolute positional encoding (i.e. the encoding indicates the exact position within the sequence) as above, and instead only comprehend relative positions[2]. Regardless, the notion of acknowledging position remains.

Diagram 1.2.2: sourced from HuggingFace, where the x-axis regards the decimal number being represented in decimal, from 0 to 150, and each sector of the y-axis represents the binary value within the 8-bit representation of the number. The orange dot indicates that the 1s and 0s on the left hand side are related to the number displayed below them; 150 = 8’b10010110.

Diagram 1.2.3: sourced from HuggingFace, attempts to depict the positional encoding where , , , where each 2 rows represent a different value for , starting from at the top.

References

[1] Introducing Llama 4 - Meta blog [2] RoFormer: Enhanced Transformer with Rotary Position Embedding - Zhuiyi Technology Co.